- Home

- Diccon Bewes

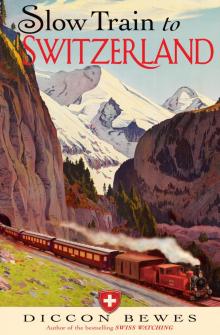

Slow Train to Switzerland

Slow Train to Switzerland Read online

SLOW TRAIN TO SWITZERLAND

For my parents, Jenny & David,

who started me off on this journey

SLOW TRAIN TO SWITZERLAND

One Tour, Two Trips, 150 Years –

and a World of Change Apart

DICCON BEWES

First published by

Nicholas Brealey Publishing in 2013

Carmelite House

Hachette Book Group

50 Victoria Embankment

53 State Street

53 State Street

Boston, MA 02109, USA

Tel: 020 3122 6000

Tel: (617) 523-3801

www.nicholasbrealey.com

www.dicconbewes.com

© Diccon Bewes 2013

The right of Diccon Bewes to be identified as the author of

this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-85788-609-2

eISBN: 978-1-47364-491-5

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British

Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any

form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission

of the publishers. This book may not be lent, resold, hired out or

otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form, binding or

cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior

consent of the publishers.

Printed in Finland by WS Bookwell.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Map of Thomas Cook’s First Tour of Switzerland

Introduction

In which we decide to take a historic tour to Switzerland

One

The Junior United Alpine Club

In which we cross paths with our fellow travellers, cross the Channel by boat and cross France by train

Two

The city by the lake

In which we go to an English church in Geneva, meet two Swiss rivers and head for the French hills

Three

Unwrapping the Alps

In which we see snowy Mont Blanc, visit the icy Mer de Glace and walk through rainy Chamonix

Four

In hot water

In which we change back from France to Switzerland, switch over from French to German and move up from Sion to Leukerbad

Five

Over the hills

In which we hike over the Gemmi Pass, watch sheep run down the hillsides and admire the Swiss tunnels under the Alps

Six

Paris of the Alps

In which we take a break in Interlaken, take a hike to the Staubbach Falls and take a trip to Kleine Scheidegg

Seven

Land of the frozen hurricanes

In which we walk to the Grindelwald glacier, stay at the Giessbach falls and travel along the Golden Pass line

Eight

Queen of the mountains

In which we get up at 5am for the sunrise on Rigi, see Lucerne in four hours and return home after three weeks away

Afterword

In which we discover what happened afterwards

A personal postscript

In which I get a big surprise

Appendix I: The world in 1863

Appendix II: Switzerland in the 1860s

Appendix III: A note on money

Bibliography

List of illustrations and picture credits

Thanks

FOREWORD

Change is a funny thing to try to assess. Often it passes by without being noticed, but equally often it hits you in the face when you least expect it. And what can be hardest is getting enough distance from events to look back and see what actually happened. Fortunately, fate sometimes plays a helping hand, giving you the chance to see into a world or time other than your own. In my case, fate came in the form of a long-forgotten travel journal that was but a footnote in some English guidebooks on Switzerland.

And that is exactly where I discovered the journal while researching my first book four years ago. It didn’t take long to track down a copy online, in a second-hand bookshop in Amsterdam, of all places. A few days and some euros later, a small package arrived in my post box: inside, a little hardback book, 126 pages long, its sky-blue dust jacket decorated with edelweiss. Not the original, of course, but an edition printed 50 years ago for the centenary of a landmark tour, one that would change a country and launch a new form of leisure activity into the world. This was a trip where women in huge dresses hiked across glaciers, where trains were a slow but exciting novelty, and where the landscape left the author almost speechless with wonder.

In a moment of inspiration or madness (or both), I decided to follow the trail that author had left behind. Guided by a woman who had been dead for well over a century, I would set off across Europe to try to see it through her eyes. Along the way, I hoped to make a personal connection with her, despite all the differences and distance between us. She had gone in search of adventure; I would go in search of her. I had her journal, so I could follow her words, but I also wanted to find some trace of her in the places both of us were visiting. It was more than about having proof that she had been there before me; it was about making the link between her tour and mine, between tourism then and tourism now – between the two of us.

And of course, I wanted to see how much had really changed since she made the same journey: not only the obvious aspects, such as journey times, but the changes you don’t really think about. After years as a travel writer, would I see what travelling was like for those package pioneers? After years as a tourist, would I learn how it all began? After years as a Brit in Switzerland, would I discover how my fellow countrymen and women helped transform that country? And had Switzerland really been so different back then? I would soon find out.

It was a tour that changed the world of travel.

It was a journey that launched mass tourism.

It was an invasion that created modern Switzerland.

It was a trip I simply had to do.

So I did.

The route of the original tour in Switzerland

INTRODUCTION

They were found in a battered tin box in the post-war rubble of London’s East End: two large books with scuffed red leather covers that had contrived to survive the Blitz intact, thanks to their sturdy container. Even then, they were almost lost, tossed aside with all the other debris from the nightly bombings. Fortunately, someone discovered them before they disappeared for ever.

Together, the two volumes make up a complete journal, an account of a trip across Europe that took place many decades before. They are written in longhand, in a lovely sloping script that is perfectly legible but delightfully old-fashioned, and occasionally illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings of foliage curling round the text. More frequent are faded black-and-white pictures and colourised postcards that have been stuck in, making it as much a scrap-book as a diary. But there is very little personal information about the author, not even her full name, or how the books could have ended up in a bombed building 80 years after they were written. As for where she went, that sounded like a challenging destination for any Victorian lady:

“We landed at Weggis, and if each man, boy and mule-keeper who attacked us had been a wasp and each word a sting, Weggis had possessed our remains. We were literally infested by, dogged and danced around by these importunates!”

&

nbsp; After those “wasps” she encountered “parasites” and “goitred ogres”, none of which exactly springs to mind when thinking of Switzerland. Yes, Switzerland, now one of the wealthiest, healthiest countries in the world. Her trip was a three-week tour of the Alps; to be more exact, the journal was an account of Thomas Cook’s First Conducted Tour of Switzerland. Not that it was the country we now know. In today’s Switzerland trains, chocolate and money are so typically Swiss that they have become shorthand for the whole country. These clichés are, however, based on fact. The Swiss are world champions in all three – per head they travel more by train, eat more chocolate and store more gold than any other country.

But 150 years ago none of them would have conjured up an image of Heidi’s homeland, as none of them existed in the same way (least of all Heidi, who made her first appearance in 1880). The Swiss arrived late to the idea of railways, so that back then there were only 650km of tracks in operation compared to over 5000km now; milk chocolate, Switzerland’s gift to the sweet-toothed everywhere, didn’t appear until 1875; and as for money, that was in short supply in a nation where many still lived off the land or from which they emigrated in search of a better life. A century and a half ago Switzerland was a very different place, where large parts of the country festered in rural poverty, and where the daily wage of an average factory worker was the same as the price of breakfast in a tourist hotel. One English guidebook from that time offered this advice to its readers:

A sou or any small coin is sufficient for the legions of beggars besetting one’s way. Make a rule of never going out without a supply of small coins, however, but never use them lavishly.

For British visitors, who were used to slums in their cities and Oliver Twists on the streets, this didn’t quite match the popular romantic image of Switzerland. It was a far-away country, although not exactly unknown territory. For decades the Alps had been bewitching writers, painters and climbers, all of whom helped transform the mountains from a daunting barrier at the heart of Europe into the natural wonder of the nineteenth century, albeit a slightly wild and dangerous one. But neither was Switzerland overrun with hordes of tourists: European travel was still largely the preserve of the rich and reckless, those with both time and money. So while Byron, Turner, Dickens and Wordsworth had all made lengthy inspirational visits to Switzerland, such a trip was beyond the aspirations of most British people, being simply too far and too expensive. The Alpine Republic was the geographical equivalent of European royalty: dazzling, beautiful and intriguing, but out of reach for normal folk, only to be appreciated from a distance. That all changed in 1863, thanks to the British middle classes and their appetite for adventure.

It would be these visitors, these bankers and lawyers, who would help revolutionise Switzerland. Their peaceful invasion provided the financial and social means for turning rags into riches. Tourism made Switzerland the Cinderella of Europe. And every Cinderella needs a fairy godmother, or in this case, godfather. That was Thomas Cook, a man who would change the world in the most leisurely way possible – through holidays.

For over 150 years the name Thomas Cook has been synonymous with travel and adventure, but before he became a global brand, he was a man with a mission. A Baptist minister from Derbyshire, he wanted the world to give up alcohol and take up travelling. While his first step down the road to worldwide recognition was organising a train trip in the English Midlands, it was Switzerland that provided him with the success needed to create the new industry of tourism. Although Thomas Cook didn’t start the trend for foreign holidays, he broadened their appeal, made them readily available and expanded their scope far beyond northern France. What until then had been a trickle became a steady stream that quickly turned into a flood that has never truly subsided – a case of all abroad!

Cook made Switzerland accessible and affordable. Trains reduced travel times and going in groups reduced the costs, so that the new middle class in Britain were able to enjoy a holiday in the Alps. His first conducted tour of Switzerland was so successful that another soon followed, then another, and another and another, until British visitors were almost as commonplace as brown cows. And the Swiss were not slow to realise the potential of this incoming tide and to capitalise on its possibilities. Hotels were built, souvenirs created and railways raced up the mountains, all for the benefit of the visitors from over the Channel. It was a relationship that suited both sides. The British got to see the Alps from the comfort of a train, sleep in a proper bed each night and go home with a nice new watch. The Swiss got to make money. It’s a love affair that has lasted 150 years and counting.

However, this book isn’t just the story of how foreign travel stopped being a luxury or of how one trip started the trend for holidays abroad. It is the story of the relationship between two nations, a tale of two countries that could not have been more different: the powerful monarchy whose empire stretched around the globe, and the small republic only just recovering from a civil war. Without Switzerland, the British may never have travelled merely for the sake of it, rather than to conquer the locals or convert them. Without the British, Switzerland might never have developed into one of the world’s richest countries.

Cook’s first Swiss tour was an engine for development in Switzerland as much as were the trains that brought him. It is thanks to him that a party of intrepid British travellers landed in France one Friday in June. It is thanks to the railways that this group could reach Switzerland in two days not two weeks. And it is thanks to both Thomas and the trains that travelling was transformed. This was the start of mass tourism and one of its participants recorded every detail.

Fast forward around 140 years and I’m standing in Newhaven on a warm summer’s day. The journal’s author didn’t have anything positive to say about the place – “There is not a drearier port anywhere than Newhaven” – but it was the departure point for Cook’s group. I could have flown to Geneva and been there in time for lunch, or taken the Eurostar via Paris and arrived in time for supper, but I wanted to follow in the tracks of that first conducted tour, and that meant taking the slow train to Switzerland. It’s no longer the easiest option but it is the original one.

I am going to retrace the journal’s route from London to Lucerne, following the same itinerary and staying in the same places (even in the same hotels if possible). Ahead lie three weeks of travelling by boat, train and bus through France and Switzerland, doing what the original tourists did each day.

I also know which guidebook my Victorian lady friend used, so both that and her diary are in my bag instead of my mobile phone and iPad. It might prove frustrating not to have the latter two, but I don’t want instant access to maps, timetables and taxis. I’ll have just the books as guides, although even with them to hand I have no idea what to expect on this modern version of that historic trip. My tour will be her tour with two crucial differences: clothing and transport. Even though she hiked over the mountains in a crinoline, I’m not going to be dressing up in Gone with the Wind gowns.

As for trains, I’ll use them where possible, even if that hadn’t been an option for her. Riding a donkey over an Alpine pass is unnecessary now that there’s a perfectly good train to take the strain; this isn’t an attempt to re-enact the trip, but to re-trace it. Indeed, railways are a crucial element of the whole picture: trains made the first trip possible and they are still an integral part of the Swiss landscape, as iconic as the mountains they conquer. Visitors take them up to get the views from the top; locals use them to come down after a day’s hiking. Switzerland without trains would be like America without cars – unthinkable.

This is a chance to step back in time and experience what it was like to be a tourist before tourism was an industry, before being a tourist became a negative concept in some people’s eyes. Grand tourists were once the greatest travellers, but now the two words have gone far beyond loose synonyms. As Evelyn Waugh said, “The tourist is the other fellow”, summing up the perception that many people have of

themselves and others when abroad. In the culture war of arrogance versus ignorance, travellers (as in people who travel rather than gypsies) and tourists view each other with such disdain that they reduce the other side to caricatures.

Travellers are seen as pretentious and patronising, looking down on anyone who stoops so low as to choose Disneyworld over riding across Mongolia in a truck full of goats. They are obsessed with going off the beaten track in the search for authenticity, but get annoyed if others do the same. Tourists are viewed as sheep who only travel in groups and rarely interact with the locals. They stick to their tick lists of sights, don’t look beyond the camera lens and usually ruin the charm of wherever they go simply by being there. Their idea of being daring is having paella with their chips.

But what if we could go back to the point when travellers became tourists – back to a time long before TripAdvisor and travel agents, when taking a train across Europe was an intrepid adventure, the trip of a lifetime for its excited participants? What if we could go where they went, see what they saw, do what they did and hear what they thought? Maybe that would change our perception of them, and us, as tourists – and of the man who started it all.

Swiss Watching

Swiss Watching Slow Train to Switzerland

Slow Train to Switzerland